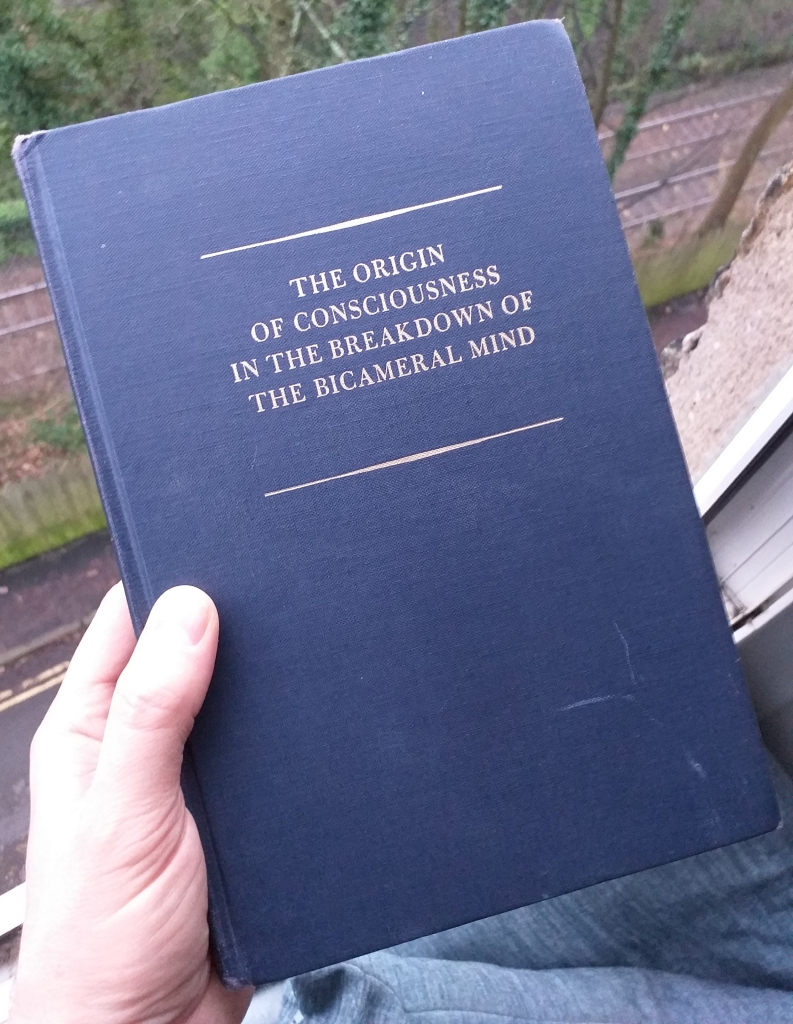

35. Julian Jaynes – The Origins of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind (1976)

A thing I’m rapidly learning from A Burroughs Syllabus is how the use of hard science in non-scientific areas (humanities, sociology, politics, religion…) works as a sort of devil’s bargain. In the short term, your argument seems far more solid and believable. In the long term, however, when the science changes, you lose all credibility.

This is essentially what’s happened to Julian Jaynes’ work.

Jaynes theory can be broken down, very roughly, into the following points:

- That “consciousness” is separate from other forms of thought, and represents an awareness of the self so modern its emergence can be witnessed in written history

- That the stage prior to this “consciousness” saw the self-conscious voice emerging like an external voice. This is what we now know as the voice of the Gods.

- Animal man and his conscious “God” were, in fact, the two sides of the brain in conversation with each other.

- This is the “bicameral mind” that Jaynes sees laying the foundations for the first civilisations only to “break down” as the voice of Gods is integrated, no longer external, and so the Gods appear to disappear and humans become nervous and self-conscious.

It’s a fascinating thesis, and its development through close analysis of the role of Gods in the Iliad and ancient Babylonian writings are sufficient to make this a highly convincing work of social and theoretical history.

The epistemology too is groundbreaking. The first chapter, in which he separates the special self-reflective capacity of human consciousness off from animal and plant levels of consciousness is absolutely worth anyone’s time to read.

And yet, very few people still read Jaynes. Why? Well, because all the brain science he uses that was so convincing in 1976 has since been totally disproven. A brain doesn’t have different areas (language centre, motor centre, etc) all “talking to each other”. Instead it’s more of a neural network, distributed like the servers that make up the internet.

Of course there was no internet in 1976, and so this model of the brain would not have been comprehensible to Jaynes. Neither have we, today, truly reached a working understanding of the brain – so everything written in our books too will one day appear oversimplistic and a bit silly.

The problem for Jaynes is that he is so reliant on the science, constantly reverting back to it when he reaches a dead-end in his reasoning, that the whole edifice appears to crumble the second you realise it’s all based on false presumptions.

In trying to excavate useful ideas from the wreckage of this once hugely popular, “ground-breaking” thesis, one has to turn his hard science theory of the “bicameral mind” into a sort of metaphor for civilisation.

Luckily, for myself, this reading is part of the Burroughs Syllabus, and so the ideal comparative text is to hand: Spengler’s Decline of the West. Spengler’s model of civilisations rising from heroes, growing stagnant, stale and finally collapsing due to effeminacy, over-cautiousness and indecision, provides an ideal paratext through which to read Jaynes’ “breakdown”.

The strongest examples that Jaynes gives are all comparisons of civilisations at their first peak and then in their first stage of decadence and decline.

In Babylonia, he compares the barked orders of the Hammurabi Code with the uncertain correspondence of the later King Tukulti. Hammurabi is shown in a carving taking orders direct from a God, while Tukulti and his God are both pictures next to an empty throne, pointing at it.

For Jaynes, this shows that the voice of their God has left them.

In Greece, similarly, we have the wild and raving heroism of Achilles and his less sociopathic but equally sporadic opponent Hector. They act when Gods tell them to and, once in motion, never question the decision for a second.

In the Odyssey, which Jaynes believes is a much later epic, Odysseus’ whole journey is based upon his “wily” mental prowess outwitting the Gods who, due to the court politics of Olympus, are portrayed as increasingly confused and unwilling to intervene on Earth.

For Jaynes, this is another evidence for the bicameral mind’s “breakdown”.

Finally, he draws on the Old Testament, with the earliest prophet, Amos, belting out his dire warnings almost against his own wishes. Many of these prophets seem genuinely uncontrollable, both in the eyes of the high priests and, in the case of some like Ezekiel, even in themselves; unable to account for their own words and behaviour.

Jaynes asks us to compare this to Ecclesiastes, whose book is all metaphysical poetry, existential uncertainty and quiet wrestling with the soul in solitude.

Between the prophets bellowing in the marketplace and the divines meditating in private, Jaynes argues, comes the “breakdown”.

But he gives it away somewhat in this last example. For, between Amos and Ecclesiastes, there is also the Babylonian captivity. Amos was raging against high priests who resided in the Temple of Solomon; theocratic rulers of a nation. Ecclesiastes was writing in solitude by necessity, for the Israelite nation had fallen and they were now the slaves of Babylon.

The historical context for the other two examples is not as stark, but – if we follow Spengler’s model of decadence coming before the fall – we can see parallels. Spengler would put civilised Babylon nearer to collapse than its early, bloodthirsty/heroic days. The same for Periclean Athens – decadent and pederastic – compared to the Mycenean’s heroic violence.

This maps as well against Vico’s New Science, with the giant, certain, violent and unwavering heroes of old giving way to intellectual lawgivers.

Seen in low enough resolution, then, Jaynes’ work is salvageable in parts. On this level it will help us to piece together a Burroughsian theory of history.

Its more wacky parts also strike a chord with Burroughs’ more outlandish beliefs. In particular, the idea that, in bicameral kingdoms, the whole of the hierarchy heard the voice of the same God in the same voice, ties in particularly with Burroughs’ belief in the Total Control of the Gods over the Mayans.

All the statues with human faces found around ancient sites, Jaynes argues, functioned essentially as broadcast speaker-systems for the Control Gods.

It’s easy to see Burroughs being interested in this. The book turns up in his “Lecture on Creative Reading”, delivered at Naropa University in 1979, where he attempts to explain it to a young student only to lose his train of thought. As such, we might predict his reading of it to coincide with the lead-up to the Cities trilogy.

The hard scientific basis for Jaynes’ work would have been of particular interest to him at this point, at a nexus point between his desire for electronic revolution and his later psychic/religious explorations. That demonic possession might be a right/left brain issue, for example, would appeal to a man whose praise for apomorphine (and later for Catholic exorcists) was remised on the human entity being “a soft machine”.